Hello everybody, and welcome back to my blog. I’m not long back from a holiday adventure up north with my wife and daughter. We stayed in a lovely apartment at Middleton Sands, near the coastal port of Heysham (pronounced Hee-shum) in northern Lancashire. This had us placed handily to explore the delights of Lancaster, Morecambe, and the Cumbrian Lake District. Of course, with it being summer, the weather veered between atrocious and slightly less atrocious, but our lodgings were comfortable and beautifully quiet. All we could hear was the curlews warbling across the sands and the thrum of the constant, westerly wind (and the sea when it occasionally made an appearance!).

Whilst we were there, I totally fell in love with the place. If you’ve read my blog before you’ll know that I am a bit of a sucker for a bit of exploration, a big sucker. I like to get lost and immerse myself in a place, and in this place you can so easily get lost.

Middleton Sands is on the Sunderland Peninsula, a wild and desolate piece of land squeezed between the mouth of the River Lune and vast, flat expanse of Morecambe Bay. The sands of the bay spread out for miles, almost to the horizon. My daughter spent a lot of the time grumbling about never seeing the non-existent sea….

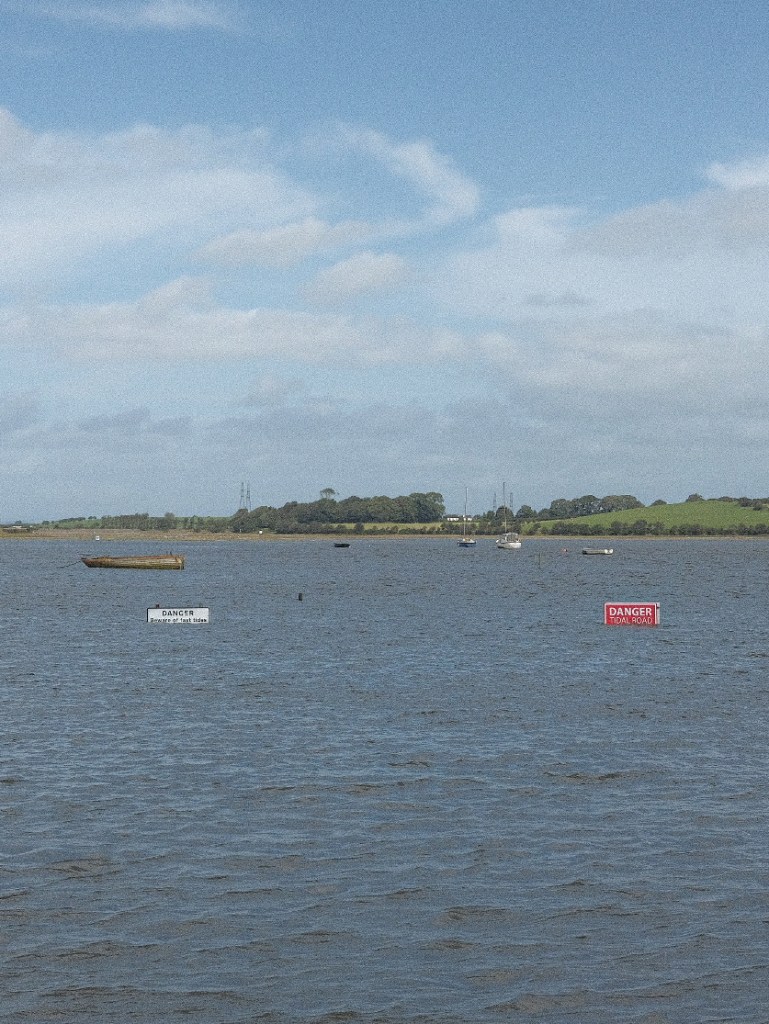

About a mile south of Middleton, perched on the very tip of the Peninsula, lies the village of Sunderland Point. This tiny village is almost hidden from the world, clinging to the windswept coast amongst salt marshes, tidal creeks and rolling sand bars. Sunderland Point is unique in the United Kingdom, it being the only mainland community that is entirely dependent upon tidal access. This is via a narrow, undulating single track road that snakes over the sands and marshes, crossing the Lune estuary to Overton one and half miles away.

The road to the village is completely submerged twice a day by the incoming tides swollen by the river outflow, cutting the village off from the rest of the county. The Sunderland peninsula is a fractious place that’s as beautiful as it is unpredictable. It’s easy to lose yourself under those luminously active skies, the fierce weather here changes as quickly as the tide. I decided that, despite the prevailing wind and rain, I’d document whatever I saw during my walks around the Peninsula.

The shores and fields around where we stayed are mostly populated by small caravan parks. It was a bit weird to see these places of leisure contrasted against such a wild, almost inhospitable shoreline and the Nuclear power station at nearby Heysham Port.

Walking south towards Sunderland Point you’re forced along the shoreline. The terrain is as treacherous as it is waterlogged, the ground cracked asunder by salt marshes and muddy creeks. Flotsam blown in by tide and storm line the shores like bleached trophies. Eventually, after dancing through rafts of cow pats and mud, you come to Hargreaves Farm.

In a field close to the main farm house is a dilapidated tram, slowly rotting away amidst an impenetrable swathe of nettles. I believe this is just the lower deck of a 1950s tram, brought here in the 1970s from Bradford. At that time, it was used as a place to live (there are contemporary photos, replete with its distinct green livery, showing it being lived in). Sadly, when the owner died during the 1990s, the tram was abandoned and has been left to the elements ever since. It was a fascinating thing to see, a homestead of abbreviated hopes and dreams, forgotten near the shore. It’s made a great subject to photograph!

From Hargreaves Farm, you continue to follow the shoreline between reminders of the peninsula’s recent past and the ever moving tide of life. Curlews, dipping amongst the sands, call plaintively across the marshes, it’s such a beautiful song.

In the distance, looking across the flat expanse of the marshes, you can see Plover Scar lighthouse amidst the shifting sands of the Lune estuary. It’s a diminutive landmark, just eight metres high, on the horizon (just visible on the far left of the photo below). At low tide, you can actually walk out to the Lighthouse, across the sands from Cockersand on the opposite side of the Lune. The unreliable nature of the marshes and mud flats here was an effective deterrent from me even considering exploring that walk! Plover Scar was built in 1847 as a low light guide for ships entering the river Lune to get to Sunderland Point and Glosson Docks, and it remains in use to this day (albeit as an automated lighthouse).

At this point our route to Sunderland Point then turned inland via the Lane. This is barely a muddy track across the headland between fields lying fallow in the weakly optimistic sunshine. We walked between wildly effusive hedgerows of field maple, hawthorn and coppiced hazel as startled hares and wary squirrels ran underfoot. It’s a lovely interlude from shoreline to riverside, where you suddenly happen upon the rear end of the village.

We arrived at Sunderland Point just as the tide was rising to its highest point. It was lunch time and yet it felt like everything in the village was still asleep. There wasn’t a soul to be seen! We walked along the riverfront, the houses here sit on a steep stone embankment that was allegedly built from stone pilfered from the remains of the dissolved Cockersand Abbey on the other side of the river. In it’s heyday in the 18th century, Sunderland Point was a busy port, trading in cotton and other less salubrious commodities (slavery being most notable). Traders would beach their boats on the shallow sands and drag their wares into the warehouses when the tide went out. The first bales of cotton ever to reach British shores were landed here at Sunderland Point.

Sunderland Point’s heyday lasted barely a century as better equipped docks and ports opened at Glosson and then Lancaster. Most of the buildings in the village date from that time and many of those are listed. The entire village clings to this strip of land that is very much in thrall to the river. All of the homes have overt and robust flood defences; when the tide is in you can totally see why! The river is less than 5 metres from your front door here, a variable and maladjusted neighbour.

The village has a rather Georgian look to it, reflecting the era it sprang up in. Big rectangular houses with big rectangular windows and big rectangular doors. Many of the houses have quite a utilitarian look about them, harking back to their original uses as warehouses and public inns. Today the village is entirely residential, there’s not a shop or café to be found here, and that’s the way the residents like it. I imagine the locals could have petitioned the authorities for a mainland road to their village, there is scope and space. But I guess it boils down to a collective feeling, this community enjoys the isolation and creative freedom that the river enforces. It is both a gift and a curse. Many cars and people have gotten stuck on the causeway, requiring rescue. And this river floods regularly, especially during the winter. Life here is dictated by the rise and fall of the tide, a double-edged sword that this community seems content to live by.

I loved exploring Sunderland Point and the wider Sunderland peninsula, it’s such a unique and fascinating place. Everyday I would take walks along the shore or across the marshes, and every walk was different. I guess the only constant was the wind. Oh my, that wind! We were there during Storm Lillian, so at times it was particularly extreme. My walk on the last morning was farcical, I could barely walk forwards onto the shoreline, so strong was the wind. It felt like walking through treacle! I found myself laughing crazily into the teeth of my own futility.

I loved exploring this place and losing myself in its rich history and remarkable landscapes. I hope you’ve enjoyed my adventures at Sunderland Point, do let me know if you’ve ever visited the area or have any stories from this place. Thanks as always for taking the time to read my blog and look at my images. I did choose a slightly different colour palette for my images, leaning into a more faded, desaturated, sea bleached look. Feedback is appreciated as always.

Till next time, be well, Jay 😀